Partitive Articles Explained on the Basis of Definite Articles

One Weird Usage Begets Another

Table of Contents

I. French Definite Articles Rationalized

French has this rule, that whenever one is talking about a thing or group of things in its (or their) entirety, one has to place in front of the name of the thing (that is, the “noun” 1 ) the appropriate form of the definite article (le, la, l’, les). This rule applies to both “non-count nouns” (which do not have a plural) –

- “mayonnaise” (as a whole, in general) = la mayonnaise

- “justice” (as a whole, in the abstract) = la justice

- “concrete” (the building material) (as a whole, in general) = le béton

- “coffee” (as a whole, in general) = le café

- “France” (name of a country) = la France

- “biology” (the science) = la biologie

- “French” (name of the language) = le francais

– and “count nouns” (names of things of which there can be more than one) –

- “French people” (as a whole, as a group, in general) = les Français

- “cats” (as a whole, as a group, in general) = les chats

- “elementary particles” (as a whole, as a group, in general) = les particules élémentaires 2

Consider these sentences, in which the French version requires the use of definite articles, whereas the English requires their absence:

- J’aime la mayonnaise. (I like mayonnaise.)

Commentary: When the French like something, they consider that they like the thing in its entirety and whenever it may manifest itself to them. Hence, similarly: - J”aime la justice. J’aime le café. J’aime la France. J’aime la biologie. J’aime le français. J’aime l’argent. J’aime les Français. J’aime les chats. J’aime les escargots. (I like [or love] justice. I like coffee. I like France. I like biology. I like French. I like money. I like French people. I like cats. I like snails.)

J’aime l’art. J’aime Paris. J’aime la France.

I love/like art. I love Paris. I love France.– Georges Pompidou (speaking in connection with

the founding of the Centre Pompidou)

Consider also these further sentences:

- La mayonnaise est un condiment qui se mange avec beaucoup de plats. (Mayonnaise is a condiment that is eaten with many dishes.)

- La justice l’emportera! (Justice will carry the day!) J’ai toujours poursuivi la justice. (I have always sought justice.)

- “Le béton associé avec de l’acier permet d’obtenir le béton armé.” – Wikipédia. (Concrete combined with steel produces reinforced concrete.)

- Le café, boisson très populaire depuis le début des temps modernes, produit des effets bénéfiques sur le corps humain. (Coffee, a popular drink ever since the dawn of the modern age, produces healthy effects on human body.)

- En 1805, l’Angleterre et la Russie se sont unies pour combattre la France. (In 1805 England and Russia combined to fight France.)

- J’ignore presque tout de l’histoire. (♫ Don’t know much about history. ♪)

- Elle étudie le français depuis un demi-siècle. (She’s been studying French for half a century.)

- Les Français adorent les compliments. (French people really like compliments.)

- J’ai peur des (= de + les) chats. (I am afraid of cats.) Tous les chats sont gris la nuit. (All cats are grey at night.)

II. French Partitive Articles Justified

French makes a very odd use of the preposition de. Combined with the definite article le, la, l’, les, contracting when it can to produce du, de la, de l’, des, 3 the combined forms can be either

- What they were before: a sequence of the preposition de and the definite article; or–––

- Something totally new and different: a determiner, called the “partitive article.”

The expression de la mayonnaise can thus be either a prepositional phrase, or a noun phrase:

- Les ingrédients de la mayonnaise sont faciles à obtenir. (The ingredients of mayonnaise are easy to obtain.)

- Il y a de la mayonnaise sur votre lèvre supérieure. (There is mayonnaise on your upper lip.)

How did the preposition de come to have this non-prepositional function? With complete unconcern about how the usage came to be historically, I offer the following logical justification.

Recall that the definite article is required when you are talking about something as a whole or in all cases. Picture such entireties as mathematical sets, represented by circles.

The circles, and the phrases beneath them, represent all mayonnaise, all concrete, all talent, all French people.

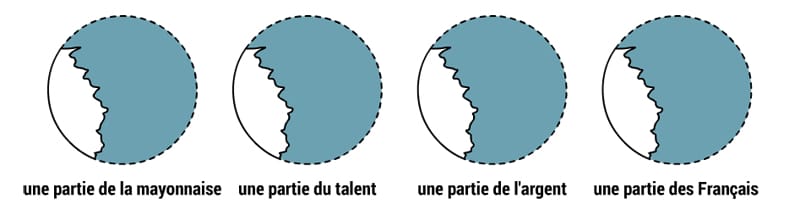

Now imagine an undetermined portion of these complete sets, with accompanying captions of the sort:

une partie de la mayonnaise

– meaning: an undetermined part of all the mayonnaise in the world:

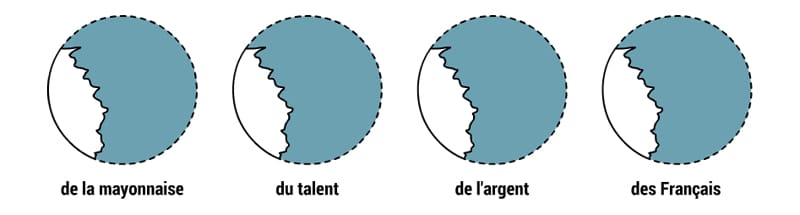

It remains, now, only to remove the first two words of the expression, une partie, but retaining for the words that are left the meaning “an undetermined part of the whole”:

Result: the expressions du, de la, de l’, des can and do when needed represent the idea “an unspecified part of a whole” (or, if you prefer, “some, any”).

Some examples for your consideration:

- La Belgique a du talent. (Belgium has talent.)

- ♪♪ “J’ai du bon tabac dans ma tabatière.” ♫ (I have [some] good tobacco in my tobacco-pouch.)

- J’ai des amis finlandais. (I have Finnish friends.)

- Avez-vous de l’argent comptant? (Do you have any cash?)

- Il y a des fées au fond de notre jardin. (♫ “There are fairies at the bottom of our garden.” ♪)

- Pour réussir, il faut non seulement du courage, mais de l’audace. (To succeed one needs not only courage, but boldness.)

- —Au contraire, pour réussir il faut surtout de la chance. (On the contrary, to succeed, above all one needs luck.)

- Il a mis du café dans sa tasse et puis il a mis du sucre dans son café. Ensuite il a mis de la mayonnaise sur son pain, qu’il a également mis, par mégarde, dans son café. (He put some coffee in his cup and then he put some sugar in his coffee. Then he put some mayonnaise on his roll, which he also, by mistake, put in his coffee.)

III. Other Article Matters

A. Leaving Articles Out

The partitive article corresponds to English “some” and, in questions and negative statements, “any”:

| French | English |

| « Je vous ai dit que je vous apporterais des pommes. | “I told you I would bring you some apples.” |

| —Et m’avez vous, en effet, apporté des pommes aujourd’hui? | “And have you, in fact, brought me any apples today?” |

| —Hélas! non; l’épicier n’avait pas de pommes et par conséquent je ne vous ai pas apporté de pommes. » | “Sadly no; the grocer didn’t have any apples and consequently I haven’t brought you any apples.” |

But quite often English can do without these indefinite adjectives “some, any.” Hence, together with the fact that English also does not use articles with general concepts or whole groups (as we say in Part I above), the overall result is that English requires articles much less frequently than French.

With general concepts / whole groups:

| French | English |

| La justice est une des quatre vertus morales. | “Justice is one of the four moral virtues.” |

| Les enfants aiment les bonbons. | “Children like candy.” |

| Cette pauvre personne a peur des (= de + les) professeurs. | “This poor person is afraid of teachers.” |

With portions of things or groups:

| French | English |

| Il a passé des années à regagner sa santé. | “He spent years regaining his health.” |

| Avez-vous des enfants? | “Do you have children?” |

| Il a du talent. Il a de la chance. Il a de l’argent. Il a de la mayonnaise. | “He has talent. He has luck. He has money. He has mayonnaise.” |

B. Reduction (So-Called!) of the Partitive Article

In certain situations – there are four in all – the partitive forms du, de l’, de la, des get what I call “reduced” to a simple de (or d’). I discuss these four in another Language File.

Three of these situations I will also examine here, for the reason that they help to explain each other. (The fourth is a mystery I long ago despaired of ever understanding.) Essentially what happens in the three is that the partitive article disappears entirely, and you are left what is actually, once again, the preposition de.

1. After Expressions of Quantity

After expressions of quantity, whether these are quantitative adverbs (if “adverb” is the right term for them here) such as beaucoup, trop, assez, peu, un peu, or units of measure such as un verre, une tasse, un kilo(gramme), un litre, une tonne (a tun), un tonneau (a barrel), etc., de/d’ appears in place of du, de la, de l’, des:

| J’ai bu du vin de la limonade de l’absinthe des toasts du lait… (I drank [some] wine, lemon soda, absinthe, toasts, milk:) |

J’ai bu beaucoup de vin trop de limonade assez d’absinthe beaucoup de toasts peu de lait, un peu de lait, un verre de lait, un litre de lait… (I drank / a lot of / much / wine, too much lemon soda, enough absinth, a lot of / many / toasts, not much / little / milk, a little milt, a glass of milk, a liter of milk…) |

It is my belief that what is really happening here is that the quantitative expression is functioning as a (pro)noun, to which the substance is attached by means of the preposition de. For instance,

beaucoup de vin

is, analyzed,

“(a) great deal of wine.”

The same applies or can or should be applied to the other adverbial quantifiers; one should think of assez de as “enough of,” trop de as “too much of,” peu de as “not much of,” and so forth. Obviously, the same goes for units of measure: “a glass of, a liter of, a ton of, three cups of.”

Now, the rule appears to be that, when the circumstances require the presence of the (honest-to-goodness) preposition de, the partitive article simply gets…thrown out. Discarded. Disappeared. One could formulate this rule thus:

The preposition de pre-empts the partitive article de + art. déf.

You can’t have both together. (Another way of looking at the matter is to say that, when the preposition de gets involved, the language reverts to an earlier stage of its existence when a partitive article was not yet required in the way it is nowadays – indeed, when the partitive article had not yet been invented or at least had not established itself securely.)

2. After a Negative Adverb

It is also a remarkable feature of the French language that after a negative adverb (they are: pas, plus, jamais, guère), the partitive article and the indefinite article (un, une) are similarly reduced to de/d’.

J’ai du tabac. → Je n’ai pas de tabac; plus de tabac; jamais de tabac; guère de tabac.

(I have tobacco. → I have no [I don’t have any] tobacco; I don’t have any more tobacco; I never have [any] tobacco; I scarcely have [any] tobacco.)

J’ai un problème. → Je n’ai pas de problème; plus de problème; jamais de problème; guère de problème.

J’ai des amis.→ Je n’ai pas d’amis; plus, etc.

It seems to me most helpful to think of these negative adverbs as analogous to beaucoup and similar quantifiers discussed above: that is, the negative particle is a kind of (pro)noun needing to be followed by the preposition de. Pas was originally (and still is, in other contexts), after all, a noun meaning “step, pace,” and the construction

pas de problème

can reasonably be thought of as something like

“(not even a) step of (a) problem.”

A similar reasoning can be applied to the other negative adverbs. The net result is: these negative particles, like the positive quantitative expressions, have to be followed by the preposition de, and so the rule give above applies:

The preposition de pre-empts the partitive article de + art. déf.

3. After Certain Verbs or Verbal Phrases

There are certain verbs and verb phrases (which here means a unit made up of a verb and a closely associated noun) that require or all but require a prepositional phrase coming after them. So, for instance, manquer, when it means “to lack / be lacking in.” You cannot simply say:

- Il manque. (He lacks.)

You have to say what the person lacks; and French requires, here, the preposition de. Observe, then, what happens to the partitive article:

| Il a du talent. (He has talent.) | Il manque de talent. (He lacks talent.) |

| Il a de l’argent. (He has money.) | Il manque d’argent. (He lacks money.) |

| Il a des amis. (He has friends.) | Il manque d’amis. (He lacks friends.) |

Similarly, the verbal phrase for “to need,” avoir besoin, also requires a prepositional phrase with de to be complete. (Literally, the phrase means “to have need of“). Note how, once again, the preposition “displaces” the partitive article:

| J’ai de l’argent. (I have money.) | J’ai besoin d’argent. (I need money.) |

| J’ai des amis. (I have friends) | J’ai besoin d’amis. (I need friends.) |

It seems to me that, as in the preceding two cases, the rule I have formulated applies:

The preposition de pre-empts the partitive article de + l’art. déf.

- Cleverly, or conveniently, the French word nom means simultaneously “noun” and “name.”[↩]

- Also the name of a 1998 novel by Michel Houellebecq.[↩]

- I consider des to be the plural partitive article. Others consider it a plural indefinite.[↩]

This was amazing. Thank you. Thank you!

You are very welcome!

Enjoyed this article and enjoy your site.

Can you solve this mystery?

Plural partitive & plural indefinite = des and seem to be hard to tell apart. Is there any real difference?

There is no difference between “des” plural partitive and “des” plural indefinite. These are just two ways of referring to the same thing. Since “des” functions like a plural of “un, une” (known as the “singular indefinite article”), some people call “des” a plural indefinite. However, it also makes sense to call “des” a plural partitive article, since it is constructed the same way as the singular partitive article ( = the preposition “de” followed by the definite article).

Merci beaucoup! I am now released from racking my brain on this.

Thank you very much. This is by far the best explanation I’ve seen.

This is literally eye -openning.

As for the 4rth case of contraction (‘des’ becomes ‘de’ before a plural adjective (j’ai des amis -> j’ai de bons amis)), I’ve come up with this explanation:

It’s because ‘les amis’ can be translated as ‘these friends’. Together with a preposition ‘de’ it becomes ‘de les’, contracted to ‘des’ for the sake of pronunciation.

But (bons amis) ‘good friends’ is a new group, independent the group ‘these friends’. And with it we just use preposition ‘de’: avoir de bons amis.

Hope it helps.

I don’t know if I completely follow your thought, but if it works for you (and for anyone else), then fine!

What a joy discovering this website – years of knowledge combined with writing craftsmanship make it both a pleasure to read and extremely rewarding for the multiple “déclic” moments.

Many thanks for taking the time to create & write these articles Prof Maddux!